heather jock bw3

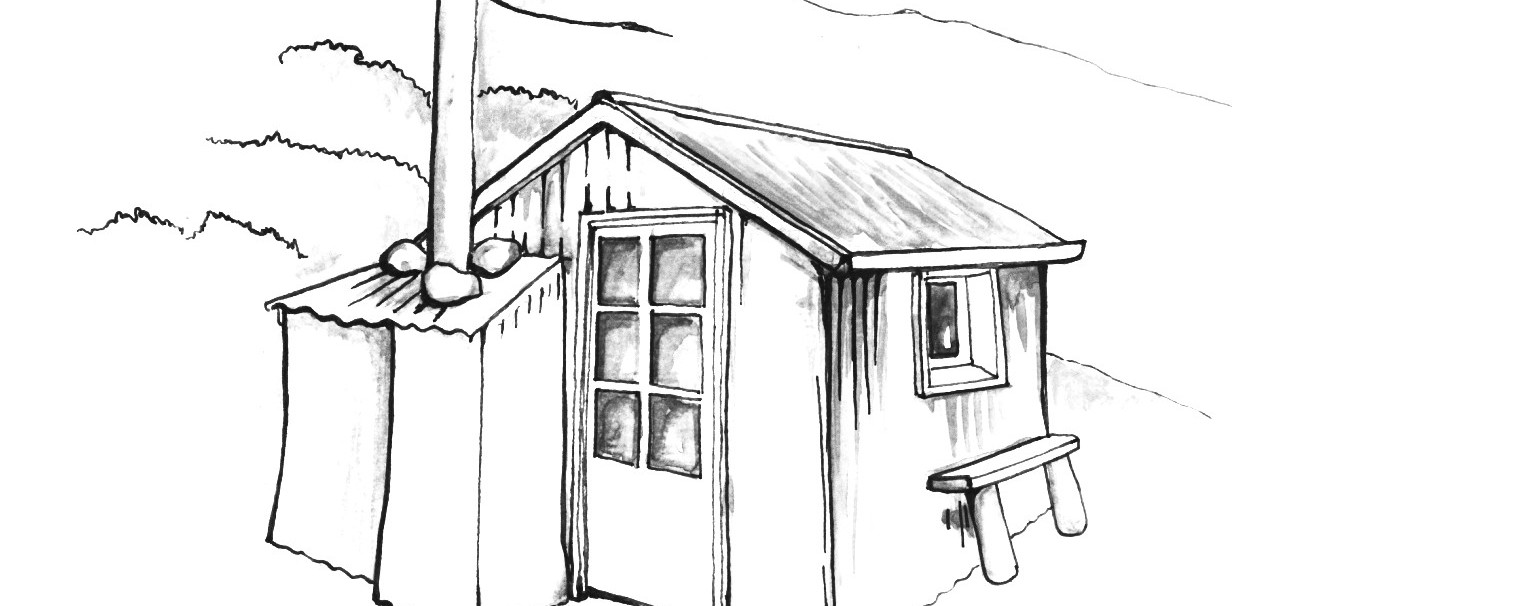

The Tramping Hut

As do many people living in central Otago, we have a soft spot for tramping huts. There's a poster on our wall cataloguing many of the smaller huts in the area. I spent a summer painting little portraits of some of these. So, like the rambles which we sometimes enjoy in the hills, here is a ramble about the delights of the common hut.

So much of that wonder is surely context. There's nothing quite like rounding a corner at the end of a long day of hiking, footsore and hungry, to see the welcome shape of a humble hut. It's easy to take shelter for granted, as we typically do with our homes and workplaces. But when you spend a little time remembering, viscerally, that you're a vulnerable mammal in a big, careless natural environment, finding the safety of a temporary home is bliss.

It also represents escape from that day-to-day world, and its stresses. We're designed to deal with stress, but not in a chronic way. Sometimes a walk is just what we need to shake it off. Sometimes a really big walk is called for. Sometimes a really big walk of several days' duration, with no cellphone coverage, hardly any other people and a whole lot of nature to get absorbed in is just the ticket. So when we remember huts we have visited, we also recall some of the moments in our lives when we've been absorbed in the present and the world's worries have, at least momentarily, lifted.

Huts tend to have a simple programme, and be no bigger than is required. This means that many of them a small, and therefore, cute. Cuteness is an almost inevitable result of smallness, although there of course is variation in this; some buildings are cute-but-almost-ugly and some are adorable. Large buildings can be all sorts of great things, but when they're ugly they tend to just be ugly, without the redemptive qualities of cuteness. There is also something intellectually appealing about being in a building which is programmatically simple, particularly when one is looking to escape from the complexity of the twenty first century. You cook on the cooking bench, sit in front of the fire, sleep on the bunk. You don't need a manual to understand that.

Huts' forms tend to be simple, as well. This is often a result of their smallness; there's no point making multiple shapes out of a space whose roof can be spanned in one go, and which can be lit with windows on one side. They're also designed with good passive-weathertightness; that is, to shed water off their pitched roofs without relying on membranes or internal gutters, which require maintenance. This leads them to have very legible shapes, which our eyes and brains can take in all at once. We seem to like that. There's a reason why so many of this region's larger homes are formed from a series of connected gables of matching proportions; it's a trick which breaks down a relatively large, complex plan and programme into a series of familiar, legible forms.

Huts are a present-day representation of a more primitive local vernacular; of the way in which we would all be building with if we didn't have quite such sophisticated materials available to us, or regulations imposed on us, or aspirations about how we live, to consider. As such, they give us a language to reference which is meaningful and relevant to us, when we want to bring a touch of that simplicity back into the buildings we inhabit. Because sometimes we do want to be reminded, as we walk up to our own front door in our everyday lives, that shelter can be bliss.