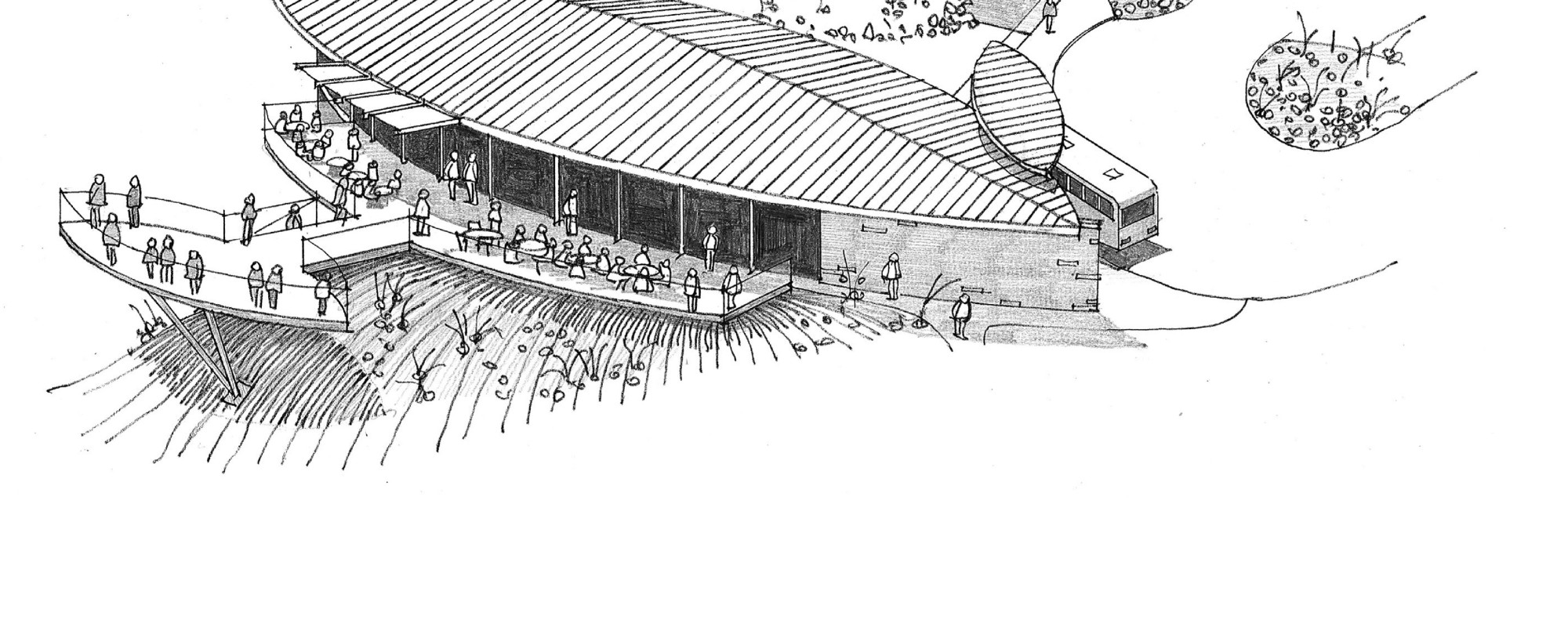

Shotover Concept Sketch by Michael Wyatt

Twenty First Century Modernism

For Architects trained in the early twenty-first century, much of our education was dominated by a movement in architecture and design generally called ‘modernism’. Its roots can be traced back to the industrial revolution in the nineteenth century, but it broke into the world in a recognisable form with the Bauhaus school in Germany in the 1920s. Persecuted and shut down by the traditionalist Nazi party, the school might have gone but its ideas lived on. In the mid-twentieth century modernism dominated the design world, and subsequent movements never quite managed to shake it off. But is it still relevant?

Superficially, Modernism heralded a move from the ponderous grandeur of the past to sleek, sexy forms. From symmetrical, brick and block edifices with punched openings sitting firmly on the earth to slender boxes clad in swathes of glass, teetering improbably on delicate steel columns. The visuals of modernism are enticing, in part because of that improbability, in part because the removal of ornament left clean, strong lines with which to form compositions, somewhat like the shapes in a Mondrian painting.

But there was more going on under the surface. This was an ideology which embraced new technologies, with the availability of structural steel freeing façades from their supportive role and allowing them to be opened up at will. Air conditioning systems meant that huge panes of single-glazing, dissolving the barrier to the outside world, were viewed as acceptable in all sorts of climates – although the thermal expectations of the users may also have been lower than ours today. Modernism asked; why we would keep doing things the same way, when we live differently, and there are new options available to us?

It was a good question. Sometimes, though, there was a good answer which was overlooked. The thermal performance of these buildings tended to be terrible, and the environmental impact of relying on energy-intensive mechanical systems to compensate for this, both in hot and cold conditions, is now clearly flawed. And sometimes these buildings struggled with their most fundamental duty; to keep the rain out. Early twentieth century Architects had gotten so used to Architectural detail being employed as fancy ornamentation for pretentious clients wanting to imitate some bygone era, they had perhaps forgotten that much of that ornamentation once had a functional purpose. From curved stone cornices to projecting window sills, many of those components were shaped around moving water off the face of the building. In other words, passive techniques for managing water ingress were discarded in favour of relying upon new impervious materials, just as passive techniques for managing thermal comfort were discarded in favour of new mechanical systems.

In our current world, where minimizing climate change through creating operationally efficient buildings is increasingly being matched in importance by creating climate-resilient buildings, that’s all problematic. But the question behind all of it still holds. Why we would keep doing things the same way, when we live differently, and there are new options available to us? The spirit of modernism, it seems, is guiding us away from an architecture which always looks like modernism. Towards an architecture which reflects the people it is made for and the context it is made in. Towards an architecture which embraces new materials and technologies alongside passive and vernacular techniques to create robust, beautiful, comfortable buildings with little energy input; towards an architecture truly made for the twenty first century.